Avocados could grow in a hotter UK – but here are the crops that will suffer

For Barry Anderson, it was hard this week to understate the level of anticipation being generated by the uniform bunches of wine grapes ripening on the sun-kissed 77,000 vines he oversees on the clay-rich soils of the South Downs.

The South African-born head viticulturist at the award-winning Leonardslee Family Vineyards in West Sussex has seen 33 vintages in his career and knows a good year when he sees one. He said: “I would compare this vintage with any of the vintages I’ve seen – it’s phenomenal. There is really beautiful fruit out there.

“For us, this is definitely one of those vintages that’s going to do down in the history books, as long as the weather remains this way until harvest.”

But while the heavy-laden chardonnay and pinot noir vines have prospered in the searing heat, Britain’s summer is rapidly becoming a story of agricultural winners and losers as extreme conditions render the 2025 harvest a lottery littered with stories of shrunken broccoli heads and dwindling wheat yields.

It is a curtain-raiser for global warming in Britain which in the coming decades could see current staples replaced by such exotica as UK-grown guacamole, marmalade, hummus and tofu.

Fewer peas and potatoes

Some 260 miles north of West Sussex, the conditions which look to set to provide England’s wineries with a vintage for the ages – the UK’s warmest spring since records began followed by a punishingly dry summer – have resulted in a dramatically different story.

James Mills, whose family have run their arable farm outside York since 1948, has seen yields from his cereal crops planted this spring fall by between 30 and 40 per cent.

He told The i Paper this week: “It’s been an incredibly disappointing year. Agriculture runs on extremely tight profit margins and if you are losing 40 per cent of your output then that will make all the difference between profit and loss. There will be some farms out there who run the risk of being put out of business by this run of extreme weather.”

Mr Mills is far from being alone.

While many farmers in the South West and North as well as in Scotland and Wales have had good conditions, growers across much of England have struggled in drought-like conditions.

The driest spring in more than a century and what is looking like the warmest summer since records began means growers of traditional UK crops – from barely and peas to potatoes and broccoli – are reporting a bitter harvest with drops in yields in some places of 50 per cent or more. This year’s drought-blighted crops compound the financial blow caused by the catastrophically wet conditions of 2024, which brought one of the worst harvests on record.

On Friday the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), a public body which monitors the UK’s main crop harvests, said the 2025 harvest had proved “extremely challenging” with “huge variability” not only from farm to farm but from field to field.

The body said the wheat yield has been nearly 10 per cent below the ten-year average and oats 13 per cent lower, adding: “Variability in the crop would be expected; however, not to the extremes that are being seen this year.”

According to the British Growers Association a 30 per cent drop in pea yields in East Anglia will see farmers struggle to recoup the cost of growing and harvesting their crop, although shortfalls in drier parts of the country are expected to be recouped by better yields either in the UK or in Europe.

On one level, the contrast in the late summer fortunes of the fruit-heavy vineyards of the South Downs and the parched wheat fields of Yorkshire seems to fit an age-old narrative of British farming – that of fickle weather inflicting years both good and bad on those seeking to feed and water an island nation.

British guacamole and hummus

But according to scientists and growers alike, extreme weather linked to global warming is already changing the face of British farming – paving the way not only for a burgeoning English wine industry but also for a transformed landscape which by the end of the century could see the pastures of Cornwall and the orchards of Lancashire given over to crops currently found only in more far-flung climes including avocados, pawpaws and citrus fruit.

The wildly variable harvest of 2025 is seen by many as a disturbing case study for a new reality facing British agriculture and horticulture as global warming starts to impose permanent and far-reaching changes on the types and quantities of foods that can be grown in the UK.

Tom Lancaster, head of land, food and farming at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, a leading think-tank, told The i Paper: “Climate change is without doubt the biggest threat to UK food security – there is an undeniable pattern emerging of extreme weather events linked to it.

“Farmers have always had to contend with the vagaries of the weather but it’s both the extremeneness of those weather events in combination with the frequency of them that is causing problems. It means farmers have no time to recover. They are used to ironing out the good and bad years. But if you don’t have good years, there’s no ironing out to be done.”

The result is a sense of urgency and no little trepidation that agriculture in Britain is facing an epochal shift. According to a Met Office study released in June, summers in the UK will be up to 5.1°C warmer and 60 per cent drier by 2070.

‘A single bad year could put you out of business’

A study earlier this year by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (UKCEH) warned that crops such as wheat or strawberries are going to be harder to grow in traditional “bread basket” regions such as East Anglia or the South East if global warming reaches 2°C above pre-industrial averages. In a plus 4°C scenario, other crops such as oats and onions will be difficult to sustain at current levels.

Experts warn that the main problem facing farming is the sheer unpredictability of the future climate as growing seasons are more routinely pockmarked by flooding, drought and storms as well as fluctuations in temperature.

Lancaster said: “It’s critically important we understand that climate change isn’t a shift from one steady state to another, warmer one. Even for crops such as grapes or berries, which have done well this year, the following year could be terrible. And for capital intensive sectors like horticulture, a single bad year could be enough to put you out of business.”

Yet, all is not doom and gloom for the UK’s ability to produce food. The success of the domestic wine industry, which last month announced it had increased the number of British vineyards by 74 to 1,104 in the last year – a 510 per cent increase in a decade – is just one example of how crops which one produced guffaws are rapidly become bulwarks of the agricultural economy.

The UKCEH research, conducted with the University of East Anglia, rated 160 new crops on measures including minimum and maximum survival temperatures and soil preferences to come up with a suitability rating for each English region.

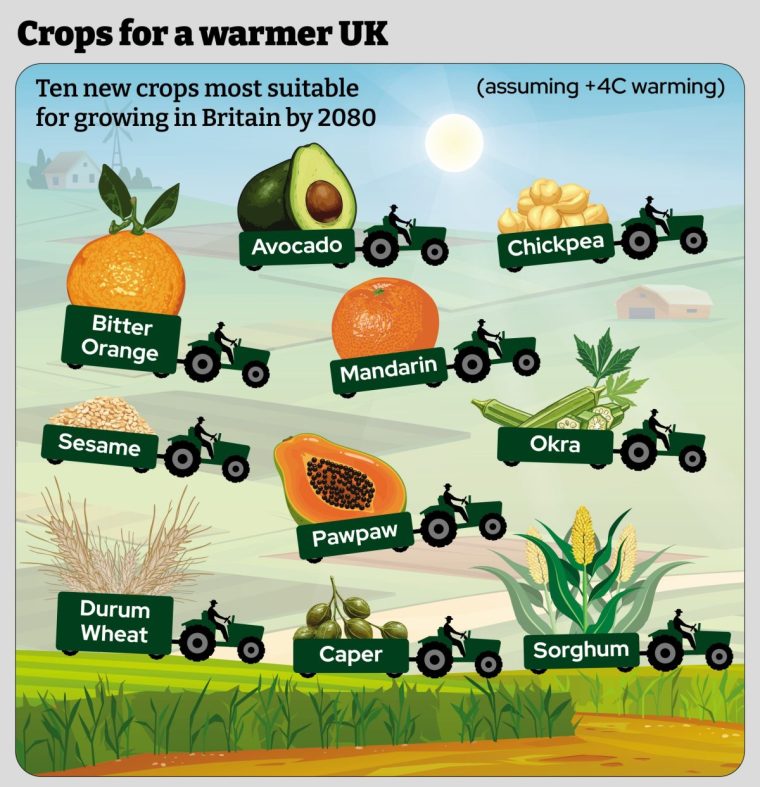

Sorghum, a nutrient-rich cereal currently grown in tropical and subtropical climes, was found to have the highest increase in suitability, particularly for growing in the South West. But a range of crops currently alien to UK fields, including Mexican avocados, okra, sesame, capers and Seville oranges, were also found to be a match for the growing conditions in locations from Devon to Durham should global warming reach plus 4°C.

Dr John Redhead, the lead author of the study, said an ability to pivot towards crops such as durum wheat, sunflowers and chickpeas – all of which are already being experimented with by UK farmers – will be essential for the British food chain in the coming decades.

He told The i Paper: “This year’s harvest demonstrates that farmers are already facing the impacts of climate change… It is vital to find ways to make UK food growing more resilient.

“Our paper shows that many current UK crops may continue to become more challenging to farm in the face of a changing climate, but it also shows that switching to new crops provides a viable way to adapt.”

Nervousness about future

The scientist is also the first to acknowledge the difficulties of shifting an agricultural system developed over centuries to a radically different template for food production.

While the west and north of the country may become significantly more viable for food production, factors like smaller field sizes and isolation from infrastructure mean coping with climate change will be far more complex than simply planting avocado groves in Lancashire or okra fields in Northumberland.

In the meantime, farmers and growers will continue to grapple with the current challenges of both climate and circumstance.

Mr Mills points out that farmers are facing multiple pressures ranging from cuts to subsidies, the row over inheritance tax and a toxic combination of soaring production costs coupled with falling prices.

He said: “The harvest will compound the nervousness that the industry is already feeling. I am an optimist and I’m incredibly positive about the industry in the next 20 years but we are going to need the government to show more support. As a nation we have woken up to the need for energy security but we are still waiting for the same commitment to food security.”

For his part, Mr Anderson has his fingers crossed for a successful grape harvest due to begin on 29 September – a full two and a half weeks earlier than usual. He said: “It’s looking tremendous. But it’s not a harvest until it’s in the tank.”

Post a Comment for "Avocados could grow in a hotter UK – but here are the crops that will suffer"